Von Enrico Giardina und Maria Cabras

aus dem Modul Schwerpunkt Journalismus 2

Im Modul Schwerpunkt 2 Journalismus nehmen unsere Studierenden am Projekt “EU Factcheck” teil. Dabei prüfen sie in Zusammenarbeit mit anderen europäischen Hochschulen öffentlich getätigte Aussagen von Politiker*innen und Lobbyist*innen auf deren Wahrheitsgehalt. Die Rechercheergebnisse werden in englischer Sprache veröffentlicht. Zusätzlich zum eigentlichen Factcheck, der sich mit einer Behauptung von Jan van Aken (Co-Vorsitzender der Partei Die Linke) befasst, entstand dieser Blogbeitrag.

Verifying numerical data is a significant challenge for many people. It requires time and effort, which are often in short supply in everyday life. Especially in areas that are outside one’s personal expertise, there is a tendency to trust the accuracy of media reports – often without questioning whether a so-called fact-check is actually correct. We, too, encountered a numerical error and were initially unable to determine whether the mistake was ours or if the sources were cited incorrectly.

How it all began

„If you invite Jan van Aken to a show, you don’t have to wait long – at some point, a number will come up“, remarks moderator Markus Lanz in a podcast (27:33). We noticed that, too. Van Aken claims there is currently no need for higher military spending, as the European NATO countries alone yearly spend over 430 billion dollars on defence, while Russia, adjusted for purchasing power, spends 300 billion dollars.

During our research, we quickly discovered that the figure cited by Jan van Aken was not entirely accurate. In none of his interviews van Aken provided a source for the $430 bn, though it seemed clear to us that a Greenpeace publication, that he mentioned in a tweet, was his source. This was the first publication to compare defence-related, purchasing-power-adjusted expenditures of Russia and NATO (excluding the USA) and coming to the numbers of $430 billion and $300 billion. And, as we are showing in our fact-check, understanding where the number for Russia came from was possible. The number for NATO on the other hand wasn’t that clear at all.

A closer look at the numbers

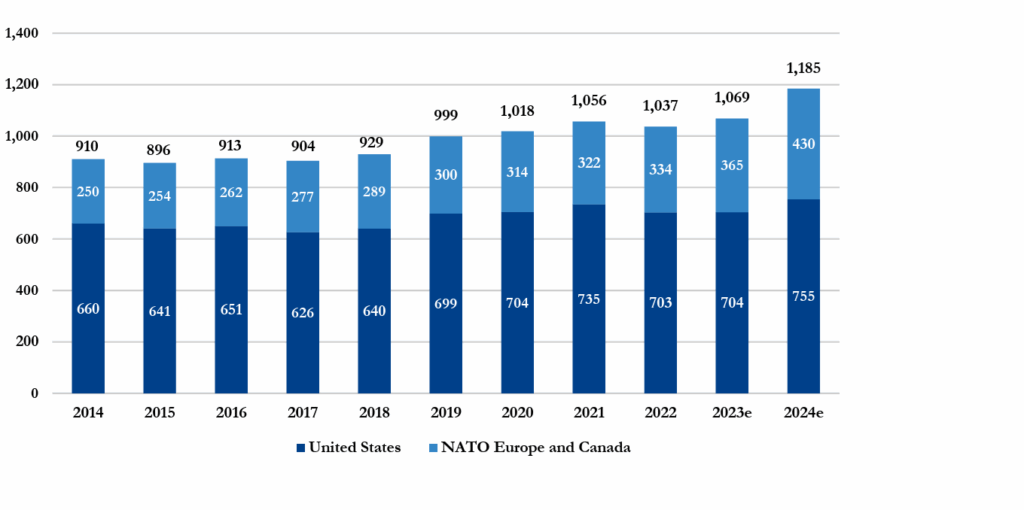

How exactly did the figure of 430 billion dollars arise, which van Aken claims are spent annually by European countries in defence? For one, $430 bn was the official NATO preliminary estimate for three months in spring 2024 until being replaced with $420 bn in June. Greenpeace’s paper only refers to the newer source, but names the older number. Also, the same rounded number appears in the cited source as an estimate for 2024 but based on 2015 prices and exchange rates. Greenpeace even cited the NATO graphic in their paper, which is why for a moment we thought, Greenpeace wanted to compare 2023 numbers to 2024.

Defence expenditure (billion US dollars, based on 2015 prices and exchange rates)

At other occasions though, starting in February 2025, Greenpeace cited the correct number, like in an article for Frankfurter Rundschau or after changing a post on their website. Nevertheless, the 430 billion dollar figure has already spread across the media and is still part of the original paper.

430 and 420 in circulation

After some research, we saw that actually both numbers, $430 bn and $420 bn were circulating, although most of the time not mentioning the year 2023 or that Canada is included. German press agency dpa for example reported on the Greenpeace study correctly including Canada, but citing $430 billion.

However, surprisingly there were also reports and press releases that cited the correct figure of 420 billion dollars. Citing Greenpeace, the correct number of $420 billion was mentioned in a committee meeting in the German parliament in March, although not mentioning Canada here. Also in taz Ilija Trojanow doesn’t include Canada but names the correct number. And even van Aken’s party Die Linke used the correct number of $420 billion in a press release dated March 1st 2025, before van Aken used $430 bn at hart aber fair and Markus Lanz days later. Generally though much more often the outdated number of $430 bn was cited, also by big media outlets.

At the end of our research, we asked ourselves how such inaccurate wording could have gone unnoticed.

Misleading fact-checks

Of course, we weren’t the only ones who wanted to take another look at these figures. For instance, Pascal Beucker, citing Greenpeace, sides with Jan van Aken in taz, stating that „when adjusted for purchasing power, the annual $430 billion of the European NATO states compares to Russia’s $300 billion.“ Focus, t-online, Kölner Stadtanzeiger and others report on discussions from TV talk shows, quoting these figures either directly or indirectly — but that’s as far as it goes.

On the website myheimat.de, for example, „citizen reporter“ Peter Gross found figures from the International Institute for Strategic Studies and concluded: „Jan van Aken is lying!“ However, these figures refer to the year 2024, whereas the Greenpeace numbers are for 2023. Moreover, they refer to all European countries, not — as in Greenpeace’s case — only NATO states. As a result, he also arrives at a figure more than 60 billion lower on the Western side than NATO itself (excluding the U.S.). So the basics are completely different, which is why the results are not comparable at all.

Why careful research is so important

Of all the media outlets where van Aken appeared, hart aber fair was the only one to publish a fact check — concluding that the $430 billion figure is correct, as it appears in NATO’s annual report. However, they did not explain that this NATO estimate was already over half a year outdated at the time — and that even Greenpeace and therefore Jan van Aken didn’t rely on that source.

This example strikingly illustrates how essential careful research is in journalism. The responsibility for spreading such inaccuracies primarily lies with the authors and editorial teams. However, the audience also carries responsibility: questioning statements critically and – if necessary – fact-checking them independently is part of the journalistic diligence that underpins an informed media society.

Beyond the numbers

And throughout the entire fact-check, we only dealt with the raw numbers. But since Jan van Aken always ties these numbers to a conclusion – namely, that more military spending is unnecessary because „deterrence is already there“ – this is where it actually becomes very controversial. Because while, despite some inconsistencies, the numbers are generally accepted as given in interviews and talk shows, and even military experts don’t question them, the conclusion is viewed very differently.

However, even the original Greenpeace study approaches this debate with more nuance than Jan van Aken presents — or is sometimes able to present given time constraints. Greenpeace explains: „The comparison of military expenditures, available weapon systems, and troop numbers clearly shows how much the NATO military alliance is superior to the Russian armed forces. […] However, these indicators do not provide any information about the actual readiness, operational capability, or effectiveness of the armed forces.“

Political scientist Carlo Masala explained to us that the Greenpeace study makes a crucial mistake by comparing armament systems purely quantitatively. „That says nothing about how Russia would actually conduct a war against Europe.“ There are areas where Russia is superior to Europe and that have high lethality. For example, Europe is very vulnerable to air attacks. Many so-called ‘strategic enablers’ within NATO are controlled by the United States. Moreover, „factors such as doctrine, tactics, morale, and leadership culture“ cannot be captured at all, yet they also play a significant role.

The military historian Sönke Neitzel explained on Deutschlandfunk (11:03), when confronted with this statement by van Aken, that Russia can „because they are only one army and not over 20, because they have a different armament system, because they have a state-run arms industry, generate much more combat power from much less money.“

At one point, van Aken countered that the Bundeswehr also maintains very expensive weapon systems that are necessary for foreign deployments. By focusing solely on national defence, even more money could be freed up. Regarding the different structures resulting from the many European countries, van Aken stated that The Left Party has long called for a stronger European security concept: „Thinking of security in European terms, pooling the money, coordinating projects!“

But even if the uncertainty over the numbers were finally resolved, the far more interesting part of the – quite controversial – debate is what conclusions can actually be drawn from them.

Mehr spannende Factchecks und Blogposts, auch von MWJ-Studierenden, gibt es auf der Website EU-Factcheck.